Maternity and paternity leave: the case of Spain in comparison with other European countries

Parental leave: Spain compared to other European countries Skip to contentNewtralMaternity and paternity leave: the case of Spain compared to other European countriesNext

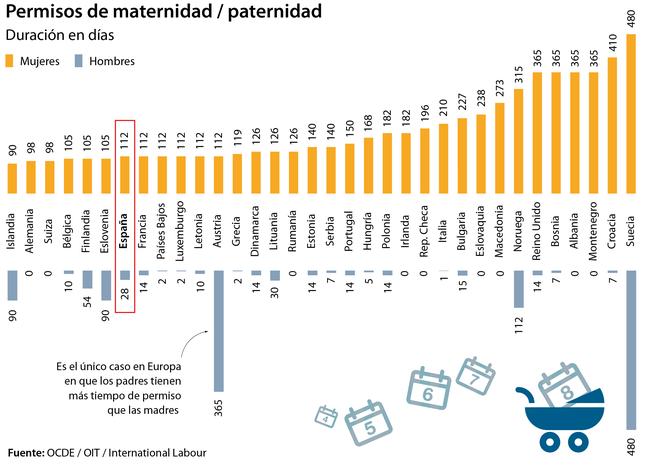

After the entry into force of equal and non-transferable permits in Spain, we analyze this model in comparison with the maternity and paternity leaves that exist in other European countries.

By Noemí López TrujilloReports |9min readImage: Shutterstock By Noemí López TrujilloReports |9min readOn January 1, 2021, in Spain the equalization of maternity and paternity leave came into force, called "equal and non-transferable" because, in addition to having the same extension, neither parent can give days to the other.

Thus, paternity leave —the one that non-pregnant fathers and mothers would enjoy— has progressively increased in Spain between 2019 and 2021. After the publication of Royal Decree-Law 6/2019, which is the one that regulates these permits, in April From 2019, paternity leave went from five weeks to eight; The Royal Decree contemplated two more increases: one in January 2020, going from eight weeks to 12, and another one this January 2021, going from 12 weeks to 16. The maternity has not changed: 16 weeks.

single mother families

Although mothers (or pregnant parents) keep their 16 weeks (that is, their permission is not extended), until now they could transfer 10 weeks to the other parent. But with the entry into force of this last modification proposed by the Royal Decree of 2019, the permit is no longer transferable (neither parent can transfer weeks to the other). In addition, the first six weeks (month and a half) are mandatory and simultaneous: that is, both parents have to take, at the same time, those six weeks as soon as the baby is born (or a minor arrives at the home, in case of adoption). . The remaining 10 weeks must be consumed in the minor's first year of life as the families decide (or they may not be consumed if they prefer to return to their job).

In this way, each parent, in the case of biparental families, has four months of leave. In the case of single-mother families, the permit, being on an individual basis, is 16 weeks, something that has sparked criticism: “Single-mother families have specific needs. It seems logical that the permits for them should be longer —as they are in some countries for multiple births—, and their remuneration should be rethought because they are single-income families”, explains to Newtral.es the sociologist Marta Domínguez, a researcher at the Institute of Political Studies of Paris Sciences Po.

The lawyer Emilia de Sousa, specializing in maternity and gender inequality, points out in a conversation with Newtral.es that "a true modification of the law" would have been to "extend to a minimum of six months for both parents, if there are two, and allow single-parent families have a support person who can enjoy the permission of the parent who has not gestated and given birth”.

For Inés Campillo Poza, a sociologist and professor at the Department of Applied Sociology at the Complutense University of Madrid, the permit equalization project brings with it “two positive things”: “On the one hand, it has placed co-responsibility in the care and fight against discrimination against women in the labor market at the center of the political agenda. And, on the other hand, it has meant the extension of paternity leave”.

However, she considers that the effect will be limited, since "it will mainly benefit heterosexual families in which both the father and the mother are formally employed and with indefinite contracts, basically civil servants and workers in large and medium-sized companies."

Thus, indirectly, “families without any member in formal employment, or in which one of its members is unemployed or precarious, will hardly benefit from this measure; neither do single-parent families”, explains the sociologist, who points out that “there are studies that show that the parents who enjoy the most days of parental leave are those who have university studies, who are married to women with university studies and who work full time” .

[Between work and life: is it possible to reconcile?]The model in other European countries

On January 1, 2021, another European country updated its parental leaves. This is the case of Iceland, which has gone from five months for each parent to six for each of them. Herdís Steingrimsdottir, professor and researcher at the Copenhagen Business School specializing in demography and gender, explains to Newtral.es that of the total for each parent, "four and a half months are non-transferable and the remaining month and a half can be transferred." Unlike Spain, where the first six weeks are mandatory and simultaneous, in Iceland this is not the case: parents can take the permit at the same time or alternate and only two weeks would be mandatory for the mother.

Steingrimsdottir considers that "the Icelandic system is close to an optimal policy", but that it could be more effective "if the remuneration for leave were increased": "Currently fathers and mothers receive 80% of the salary [in Spain it is 100% ] up to a limit. The cap used to be higher before the financial crisis, and men seem to be more money-conscious when it comes to taking parental leave than women,” she adds.

The international Leave Network collects permit models in 45 countries. In its latest report, from 2020, the disparity between countries is observed. For example, in Italy, mothers have 20 weeks (five months) that are compulsory and one compulsory week for the father, which can be used in the first five months after the birth.

In the United Kingdom, the mother has 52 weeks, although 13 of them are unpaid; and parents can choose between one or two weeks. For them, permission is not required; for them, only the first two weeks (four if they work in a factory). Therefore, the remaining, non-compulsory 50 weeks of maternity leave can be transferred to the father.

And in France, according to the Leave Network study, maternity leave is 16 weeks (26 if the surrogate mother already has two children) and is mandatory, that is, women cannot return to work earlier if they wish and They would also not be transferable. In the case of parents, their leave is two weeks (the analysis does not indicate if it is mandatory, only that it must be used within four months after the birth of the baby).

According to a study by Finnish and British researchers —published in 2019 in the scientific journal SAGE Open—, Finland was "the first country in the world to introduce paternity leave." Here, the maternity leave is 105 days (almost 18 weeks, taking into account that the working weeks are from Monday to Saturday) and the paternity leave is half: 54 days (nine weeks). Of those nine weeks, the father can take three at the same time that the mother enjoys her permission. In addition, Finland contemplates an extra parental leave of 158 days (26 weeks) paid at 70% of salary and that parents can divide as they wish.

Alison Koslowski, professor at the University of Edinburgh and researcher specializing in parental leave, gender and the labor market, explains to Newtral.es that “in Europe there is no single model”: “There are models that still assume that the mother is the main caregiver , cases in which the maternity leave is longer, of several months, but that of the parents is only one or two weeks with a transferable part by the mother”.

According to Koslowski, “the evidence shows that parents are much more inclined to take leave when it is an individual and non-transferable right”, although he considers it important to implement other public policies that are not only focused on the labor market: “The reduction of the working day would be a good way to allow conciliation”.

[Around the four-day workweek: Work one day less or work less each day?]Simultaneous parental leave

One of the notable aspects of the recent model implemented in Spain is the obligation to simultaneously apply part of the permits. Thus, at least one month and a half of the total of four months available to each of the parents must be consumed at the same time.

The political scientist Sílvia Claveria, a researcher at the Carlos III University of Madrid and specialized in gender inequality, points out to Newtral.es that the evidence indicates that "both parents enjoy this permission from the beginning —and individually— it helps to create routines from the beginning and not just become 'helpers'”.

“It has been shown [Claveria cites this study] that even in egalitarian couples, once a new member arrives in the family, the time dedicated to these responsibilities is unbalanced,” says the political scientist. In this way, the roles would be settled, producing a specialization of domestic work: “For women, as they have had maternity leave from the beginning and for a longer duration, the responsibility of doing the new tasks is naturally assumed. . In addition, since they have done them from the beginning, they are more efficient doing them”.

Sara Moreno, sociologist and researcher at the Autonomous University of Barcelona and specialized in conciliation and inequality policies in the labor market, also points out the importance of simultaneity, but clarifies that "if it goes on for a long time, there is a risk that parents do not assume the role of caretaker: “If it is prolonged, the man will develop his role of support or helper, not caretaker. Often, when they are simultaneous, they use the permission for other things: for example, the academics who take advantage of that time to be more productive and get on with the papers that they had not had time to do”.

In this sense, Moreno defends that the permits be equal and non-transferable, but that the simultaneous part be two weeks, while the mother recovers from childbirth. Although she acknowledges that "not all women recover at the same time and in the same way": "The truth is that there is no perfect public policy in its design."

For the researcher Alison Koslowski, from the University of Edinburgh, "it is essential that parents spend time alone with the baby": "A simultaneous part of the leaves could be beneficial for the relationship between family members and useful if there is more children at home, but for gender equality and for them to learn to care, it is important that a good part of the leave is not simultaneous”, she adds.

Also Johanna Lammi-Taskula, director of the Children, Youth and Families unit at the Finnish Institute of Health and Welfare, shares this vision: “It is important that parents have their own turn so that they take full responsibility for the care of the baby and do not become just an assistant to the mother”, he points out in a conversation with Newtral.es.

Lammi-Taskula notes that during this "home alone" period, "many parents learn new skills as skilled caregivers." This specialization in care work on the part of both could prevent future problems. According to this Finnish researcher, “mothers who are absent from the labor market have very low incomes, which results in very poor pensions; and parents who don't spend time with their children in pursuit of their careers then try to make amends with the grandchildren."

Equal or broader permissions for mothers?

Another of the aspects discussed about the Spanish model is that paternity leave has increased significantly in recent years without any change in maternity leave.

Libertad González, professor of Economics at the Universitat Pompeu Fabra and researcher specializing in the workplace, tells Newtral.es that "the reform of paternity leave does not question the labor market", but points out that "very long maternity leaves unhook to women in the labor market.

For González, “only with this type of policy the changes are not very big for gender equality”, but she advocates equalizing permits as “it is the only way that men are also co-responsible”.

The sociologist Sara Moreno also points out that "the status quo is reinforced from the productive logic because it favors greater labor availability before greater availability for care": "But let us remember that this is implemented within the framework of labor rights, it is not a universal right. In fact, it only favors those people already linked to the labor market”.

According to Moreno, “empirical evidence seems to indicate that it is good for permits to be equal and non-transferable”: “When the permit is transferable, it ends up being taken by more women than men. Then it would be necessary to see what use men give to these permits. The point is that a public policy is designed for the incentives it can generate, but you can't control everything”.

Lawyer Emilia de Sousa points out that equal and non-transferable permits (and for only four months) obviate the "biological dimension of pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum": "Proposals as interesting as temporary disability after birth have not been taken into account." delivery whose basis is the physical recovery of the person who has given birth: for example, 15 days if it is a delivery and one month if it is a caesarean section. It is incomprehensible that in Spain you can take sick leave for a minor intervention, but you cannot take it for a major surgery [cesarean section]. And the permit should start right at the end of this drop because its fundamentals and its destinations are very different”.

For her part, the sociologist Inés Campillo considers that speaking of rights associated with a physiological process "does not imply defending that women take better care or should take more care because they are the ones who gestate and breastfeed (if they so wish)": "It is more or to recognize the difference that 'putting the body in' means and protecting certain situations (for example, the possibility of breastfeeding up to six months). In this country, women and pregnant people who have children are neglected and neglected once we have given birth.

For this reason, Campillo considers that "it would have been a higher priority to introduce a universal benefit for a dependent child or universalize maternity leave so that those who are unemployed without benefit, inactive or do not have sufficient contributions" can benefit from this right.

128 LikesMost viewedNewsWho supports whom in the conflict between Russia and Ukraine, on a map VideoNewsHow to do a reliable pharmacy antigen testNewsCalculate your pension in 2022 with the new revaluationNewsYou ask us about the positive antigen tests with water, beer or soft drinks: they are poorly doneNewsIt is false that outdoor masks are not mandatory as of January 24NewsYou ask us about the test that combines the detection of COVID-19 and flumsnHow much does an antigen test cost at the pharmacy? High demand and distribution delays affect price ahead of the holidaysFakesNo evidence of 46 child deaths from Pfizer vaccine in the US8 Comments

Paco says:Why do you show only 5 countries, in addition to the most delayed in this regard. Mention in Central and Eastern Europe that they are between 1 and 2 years off with full salary. Here the ridiculous 16 weeks. That is a social country? A lot of feminism and "boys and girls" but the baby at 6.5 months, to the nursery.

ReplyShanti Pérez says:Why if 80% of families formed by a single parent who is female have to be called single parent? Why do we live in a patriarchal society that has adapted the use of language to its androcentrism? Because a patriarchal institution such as the RAE says so? An institution of more than 300 years, with 4,885 members throughout its history, of which only 11 have been women. Why if women are 50% of the population, is this not reflected in an equal use of language? My son grew up in a single-parent family and although the RAE or sursuncorda does not recognize it, I will continue to use this term for my family and for all families that have only one parent in their family nucleus. I don't care if the Minister for Equality is called Irene Montero, Soraya Sáez de Santamaría or Carmen Polo.

Answer