Haitian migration continues for Mexico - Catopardo

Sleepy, in flip flops and shorts, Joseph Remy Julien wears a bucket to the water intake in a kitchen built outdoors. While waiting for the container to fill up, a woman carves clothes in a makeshift sink with a plastic sink on a wooden bench, a child brushes his teeth next to an old stove that doesn't work and, right there, another woman scrubs the large pot in which they cooked Guatemala-style barbecue the day before for the 150 people who live in this migrant shelter called Little Haiti. Shortly before seven in the morning on this last Sunday in June, the morning toilet ritual has begun.

Joseph Remy—or just Remy—doesn't interact with the rest. It may be because his Spanish is incipient or because he is still half asleep or simply because he is not interested in doing it. When he finishes filling his bucket, he hands over to the next user, navigates a muddy, muddy path to one side of the kitchen—a maze of clotheslines with hanging clothes—and heads to his room to clean up away from the hustle and bustle.

This jovial but shy Haitian, who looks younger than his 53 years, has four children waiting for him in Haiti, where he fled in 2016 in the wake of the political crisis. He migrated to Brazil in search of work, where he lived for three years, and when he lost his job there he went to Ecuador. After a year and a half, he arrived in Mexico, in April 2020, with the intention of seeking asylum in the United States. In Tapachula, Chiapas, near the southern border, the government issued him a visitor's card for humanitarian reasons and with it he crossed the country to the northern border; in Tijuana, Baja California, he had to wait a turn to start the asylum process and wait, in accordance with the immigration policy implemented by the administration of Donald Trump and the government of Andrés Manuel López Obrador, the Migrant Protection Protocol (MPP, for its acronym in English) or also known as the “Stay in Mexico” protocol. A few months later, in July of that 2020 and in the midst of a pandemic, his visitor's card expired. Now Remy says that without her no one would give her a job. Show the expired card, open your arms and raise your shoulders.

—Without a card I don't work, I don't work. They sell twenty, twenty-five thousand pesos, permanent. But I don't work, I don't work,” he repeats several times, in difficult Spanish, to explain the entanglement of his situation: they have offered him regularization for an amount of money that he neither has nor can save, precisely because he is unemployed.

He arrived in February 2021 at this refuge founded by Haitian migrants five years ago, one hundred meters from a Christian temple, Embajadores de Jesús, on a piece of land spread out on a hill. Initially, he spent the night on a cot inside one of the two cellars with tin roofs where between seventy and one hundred people sleep in each one. He shared the space with compatriots and other Central American migrants. But, as the months passed, little by little the Haitians began to leave and the Honduran, Salvadoran and Guatemalan families that arrived with the flow of caravans occupied both ships and reconfigured the spaces in the shelter. Soon he was able to move into one of the wooden rooms next to the kitchen. Central American migration increased from November 2018, the year in which the College of the Northern Border (El Colef) documented the arrival of at least six thousand people seeking asylum. Now they are the majority in this migrant community.

Little Haiti is a hostel. The idea to build it came from a group of Haitians who arrived in Tijuana in 2016, stuck on their way to the United States, and from Gustavo Banda, pastor of the Embajadores de Jesús temple. They wanted to create a housing colony on the land next to the church that they occupied as a shelter. They would build their houses and create a little Haiti in the north of Mexico. But the development project remained just that, an idea, and they ended up building only a few rooms and the two warehouses, with the monetary and in-kind contributions they received from the citizens. Throughout five years the migratory circumstances were modified; Central Americans began to arrive in 2018 and, more recently, migrants from the interior of Mexico. But the Haitians got jobs that allowed them to rent and stopped living there or stayed for a couple more years and, although they seemed to have settled, at the first opportunity they decided to leave.

Remy shares a room with Benicais Cadilus, 66, who is a solo traveler like him, and his immediate neighbors are a couple, Mirlene and Edmond Pasteur, 38 and 41 respectively, with whom he speaks the same language. The four are the last Haitians in the area: some unemployed, others with unstable jobs, have not been able to regularize their situation and cannot afford a place to sleep.

"Haitians aren't coming to Tijuana, they want to go to the United States," says Remy.

CONTINUE READINGJessie and Jessica pose for their portrait.

***

At the entrance there is a gate that announces: “The person who does not live here cannot enter” and, on a mound of earth supported with tires, stands a sign that announces: “Iglesia Embajadores de Jesús. Little Haiti. City of God".

First the temple was built, a rectangular concrete brick building the length of a football field, with a high tin roof and modest finishes. Then, on the adjoining land, they planned to build the rest and they started with a couple of wooden rooms that were intended to be homes. The development did not prosper because they did not obtain the necessary permits from Civil Protection, which described the land as inadequate. In the end they only managed to raise those rooms and the two buildings behind them, which look like warehouses. Currently, both spaces function as dormitories that house almost eight hundred migrants of different nationalities.

Although when googled it is still located as Little Haiti, Gustavo Banda already refers to this place as Little Central America. A man who defines himself as a missionary, an academic from the Department of Economic Studies at El Colef, tall, stocky and with an imposing attitude, the pastor moves between the two hostels, stopping every once in a while to solve a request from his guests like the leader he is, giving Orders to those who support him to organize the daily life of this space, receiving donations in kind or members of altruistic organizations that attend to give free medical consultations, among other services for migrants.

She recounts that she was finishing building the temple when a prophet friend from her congregation told her: “The nations are going to come to this place.”

—People thought I had gone crazy. We had to build it, I didn't know why, but we had to finish it. In the world they can call it a hunch. I knew I had to finish it," he says among the bustle of the families that live in the temple.

Gustavo Banda lives with his family in this neighborhood, Cañón del Alacrán, on the urban limit of Tijuana, among earthy hills, where eleven years ago they lacked basic services such as electricity, drinking water or drainage and the few neighbors who had accumulated their garbage for the pigs to graze on. Now they already have services, although the drainage is deficient; the main street remains unpaved and becomes a sewage canal when it rains, while the garbage and pigs, along with the fetid smell, are still there.

In that canyon, with donations and contributions from believers, he finished building the temple in 2016. Migrants soon arrived: first it was Haitians, then Central Americans and now, also, countrymen fleeing violence in Mexico, what has meant that the space has been —and is to date— occupied as a temporary bedroom for hundreds of people.

—No one thought it would become a shelter. But a migration of twenty-two thousand Haitians arrived. For reasons of God, gods, they came to this place.

But the Haitians did not arrive on their own.

—I had a dream in which I saw a dark-haired man, I'm not going to say he was Haitian, because I didn't know. But he said that I had to go look for him, because that man spoke my language and was going to bring them all.

That man, as he deduced, was a Haitian named Hosea —as one of the first prophets of the Old Testament, representative of God's mercy and hope for the future—, although he learned that later.

Salomon, a 28-year-old Haitian migrant, in the makeshift camp at the El Chaparral border crossing.

***

The exodus reached Mexico in the second half of 2016. In September, the National Migration Institute (INM) reported the entry of at least fifteen thousand foreigners through the southern border. "The flow of migrants originating from Haiti was in the majority and became increasingly important, until it represented 80% of the flow in December 2016," indicates the special report of the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH) and El Colef. Of these, half entered the United States to request protection and 3,400 stayed in Baja California: 75% in Tijuana and 25% in Mexicali. The Survey of Migrants Sheltered in Tijuana found that nine out of ten Haitians who arrived in the border city came from Brazil, traveled by bus, plane, boat and on foot, crossing eight to ten countries in a journey that lasted at least three months.

International organizations consider the earthquake of January 12, 2010, with a magnitude of seven degrees, as the origin of this massive emigration in the recent history of Haiti. The island already had the lowest human development index in Latin America and the Caribbean at that time, and the disaster only accelerated its social deterioration and insecurity; access to educational and health services fell, causing the forced displacement of 1.5 million people, according to the International Organization for Migration (IOM). In subsequent years, some countries adopted humanitarian reception policies, such as Brazil, which began issuing work visas for them with a minimum of requirements. By the end of 2014, it was estimated that the number of Haitians living in Brazil was greater than fifty thousand. Two years later, the economic crisis in the South American country that led to the dismissal of its president, Dilma Rousseff, and the loss of a large number of jobs, triggered a new migratory exodus to the north of the American continent. In addition, the suspension of the Temporary Protected Status (TPS) of the US government was added, which existed precisely as a result of the earthquake and with which Haitians could obtain work permits. Its suspension, at the end of the Obama administration, resumed the deportations of all those who entered its territory irregularly.

The scenario was further aggravated by two whirlwinds. First, the impact of Hurricane Matthew on the island, in October 2016, which caused the death of six hundred people and economic losses of 2.7 billion dollars, equivalent to 32% of Haiti's GDP, according to the UN report. And second, the one that generated the beginning of the administration of Donald Trump, in January 2017, with an anti-immigrant speech that finished specifying the adverse conditions to dissuade many from their attempt to enter the United States and that, instead, settle in Tijuana, at least until it was safe to cross.

Benicais Cadilus, 66, pictured in Little Haiti.

***

One Saturday afternoon, Pastor Gustavo Banda decided to go to the center where he had heard that the Haitian migrants were gathering. At that time the arrival of hundreds of foreign families was already evident in the city and, in response to his dream, he wanted to invite them to the temple. Remembering that moment, “here suddenly one day, it was September, it was October 2016, we woke up like this, with a lot of people, and I'm going to tell you like this, blacks, on the street. Nobody knew where they came from or anything,” says Soraya Vázquez, current deputy director of the organization Al Otro Lado, who participated in the Tijuana Humanitarian Aid Strategic Committee, which sought to respond to that first migratory wave.

The hundreds of migrants, mostly Haitian, but also a good number of Africans, congregated in the southern area of the El Chaparral checkpoint —at the San Ysidro border crossing—, a kilometer and a half from the border , in the surroundings of the Padre Chava Salesian Breakfast Area, the first place where civil society began to attend to the immediate needs of food and shelter. The newspaper El Universal reported in October the discontent of some merchants in the area, upset that the migrants who slept on the street, in front of their businesses, gave a "bad image to their stores." The owners yelled at them: "Go away, black!" However, in general there was empathy and solidarity among the people of Tijuana, attitudes that, in part, were built thanks to an information strategy and later, to the work of social integration carried out by the Strategic Committee. The migrants arrived with the INM official letter from Tapachula to wait their turn to request asylum from the US government. The Animal Político portal published that, in addition to Tijuana and Mexicali, they moved to San Luis Río Colorado, Sonora. At that time, it was said that most of them went to the border with California because in Arizona there were "racist groups that hunt them down." The asylum process, given the number of applications, could last weeks or months; While waiting, the families slept outdoors, a situation that placed the problem at the center of social attention. “We are talking about the fact that around sixteen thousand people arrived here, at a time when the city obviously did not have the infrastructure to serve them, nor did the government, a strategy,” explains Soraya Vázquez.

This is how pop-up shelters emerged, as they were called, which were churches or spaces not designed precisely for that function, with the intention of helping in humanitarian emergencies. After El Desayunador, the Embajadores de Jesús church was the second space that housed the largest number of people: more than three hundred, according to reports by the CNDH and El Colef. Gustavo Banda believes that his idea of inviting Haitians to his temple was successful because many of them, he says, were Christians—Haiti's second-strongest religious group—and were eager to attend a service. The first day they received them, the pastor and other parishioners had to make several trips in trucks to take all those interested to the Embajadores de Jesús temple.

—Pastor, look out, because we have a problem, they tell me. -What is the problem? —That we already brought the two vans full of Haitians. —Well, how soft, right? —No, that's not the problem: it's that there are more than a thousand and they all want to come to church.

There was also another problem: hardly anyone spoke Spanish. Inquiring, the destination appeared again. The exception was a Haitian who, before arriving in this country, had been in the Dominican Republic, who offered to translate the service into Creole or Haitian Creole, a language that arose from French mixed with African languages and which is the official language of Haiti along with the French. The translator was called Hosea, the one from the dream.

—I think that man preached something totally different, I didn't understand him. Because he preached so well that everyone applauded. I was supposed to preach and he translated and it was a very nice service.

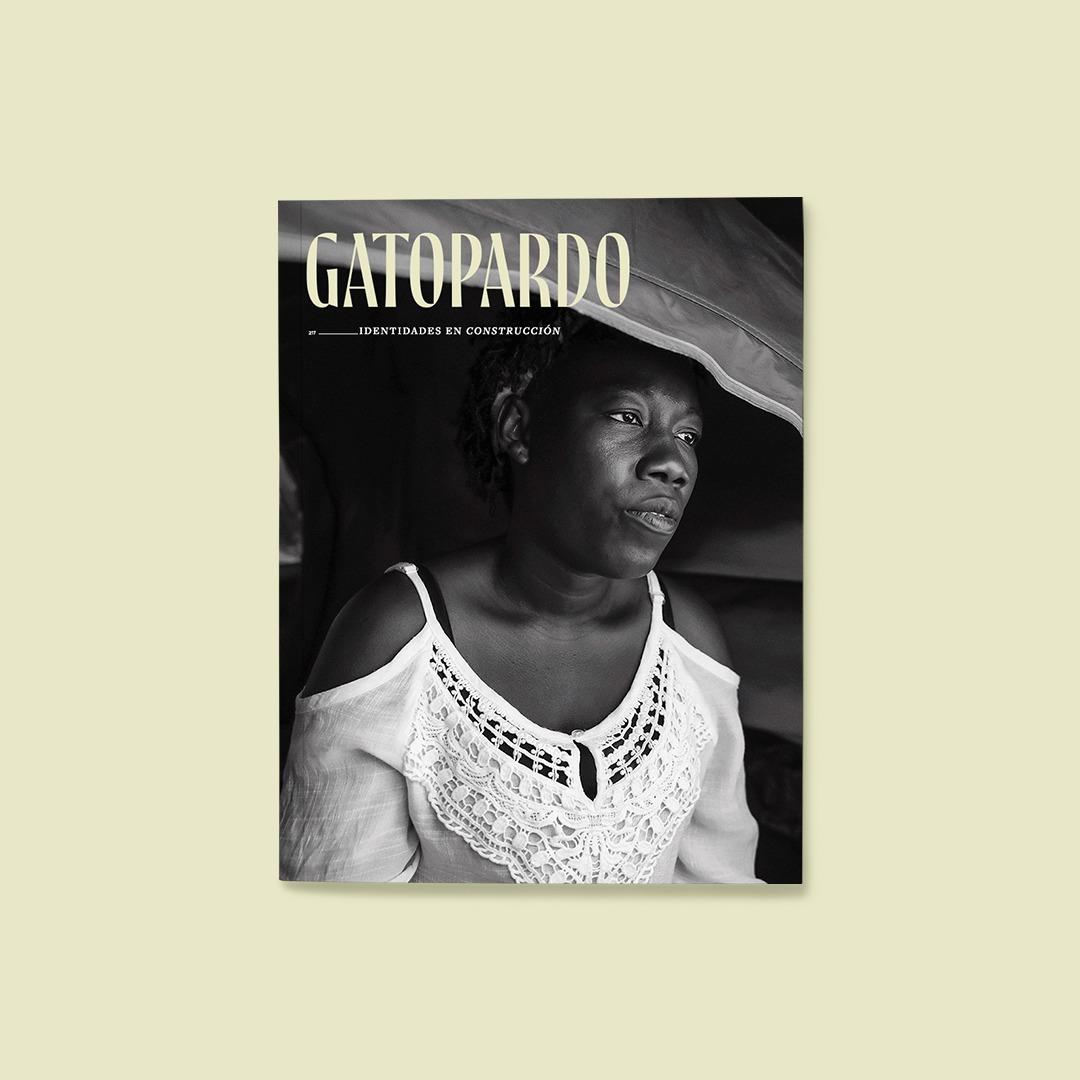

Nathacha Augustin, a 43-year-old Haitian, first migrated to Chile and then traveled to northern Mexico.

***

Cross ten countries to reach a destination. Travel by water, by land, by bus or by boat; cross jungles that emanate the stench of the decomposing corpses of those who did not manage to finish the path; hide from authorities and criminals in dumpsters; knowing the best and the worst of people as you pass through unknown places: without a doubt, an experience that forges anyone.

***

—It's long, do you want to hear it? It's a long story — warns Ivenson Jasnel Dorne.

Now that Jasnel has settled in Tijuana, after crossing ten countries in Latin America, having turned twenty-seven and married, he maintains a positive attitude: he is constantly smiling, joking, charismatic.

—Hello, how are you? Here we go! —he energetically greets the Mexican owner of the La Casita de Ale food joint, who is actually his aunt-in-law.

He was twenty-three years old. She had finished a degree in languages; He was a volunteer translator, a musician, he gave guitar lessons, he fixed computers, but he couldn't earn enough income to survive. He decided to leave Haiti, where his father and brothers stayed. He took advantage of the facilities that the Brazilian government gave to his compatriots and applied for a work visa, which was granted shortly after. So in Brazil the exodus began.

—There was no chance. Because the country has remained like this since [the earthquake and hurricane of] 2010 and, well, the government's poor organization. So the country was going downhill, a lot, and one was finishing his degree, because he couldn't work. So the solution is to leave the country,” says Jasnel.

He remembers from Brazil that people were very relaxed. From Peru, motorcycles. From Ecuador, it was cheap. From Colombia, that there were more black people and that made it easier for him not to be detected. From Panama, the greatest of his challenges: the walk of days, crossing the jungle that smelled of death. From Costa Rica, the good reception of the people. From Nicaragua, which was the country that treated him the worst: they did not let him pass and a coyote charged him three thousand dollars to do so. From Honduras, who was robbed and nobody did anything. From Guatemala, which passed without problems. From Mexico, the kindness with which a family welcomed him in Tapachula and the cold in the area of La Rumorosa, in Tecate, shortly before arriving in Tijuana, almost five months after the start of the trip.

—The road you want to get to is the United States, but the reason is Mexico because Mexico borders the United States.

He arrived at the Baja California border on December 4, 2016. The first night in the city that is now his home, he slept on the street. The Mexican authorities sent him to a shelter; then the Americans gave him a date—January 28, 2017—to cross and apply for asylum. But it would be too late: the new administration, that of Trump, prevented him from passing.

—Since they didn't let us cross, Mexico begins to offer us opportunities here. What does Mexico do? Immigration in Baja California gave us paper. They told us: “Stay here, there is a lot of work here, you can stay here, there is no problem, you can study”. And they gave us a piece of paper, it was a visitor's card. We are all looking for how to integrate into the community, but the hardest thing was how we were going to work if we didn't know any language. We didn't know anything.

Araceli Almaraz Alvarado, a researcher at El Colef's Social Studies department, identified language as one of the main barriers to the integration of Haitians into the city and created the Oral Migration Archive project in which student volunteers gave classes of Spanish and English to migrants in shelters, between 2016 and 2017. This is how Jasnel and others managed to learn the language, which facilitated their social, cultural and economic integration, considers the academic. After a few months, Jasnel got a job as a French teacher, stopped living at the hostel, and after three years received permanent residence. In June 2018, with his own resources and from home, he created Radio Haitiano, a station that can be heard on the internet, aimed at the Haitian immigrant community in this city. He is a broadcaster, music program and gives news related to events in the Caribbean and information on relevant immigration issues. A year later, he married a woman from Tijuana and had a daughter, which ended up rooting him in Tijuana.

—Life has never been easy. The easiest is expensive. Life is a struggle itself. You have to fight to get ahead. Where are you?, where are you going to be? and where do you want to go? Every time I think about that path it makes me want to get ahead with my life,” he reflects.

The young Haitian has adapted to what the country has offered him. Among his immediate plans is not leaving Tijuana. That "ultimate goal" has been reconfigured since he is the husband and father of a one-year-old girl. Currently, she wants to save to open a Haitian restaurant that offers the typical fried chicken with rice, beans and salad, distinctive of its cuisine. Also, he says, he will soon carry out the process for Mexican nationality.

“The good thing about us Haitians is that we adapt to where we are, we do what we are allowed to do,” says Jasnel, with the conviction of someone who settles where they allow them to have a home.

Jasnel, 27, French teacher.

***

There is a psalm that forty-year-old Nathacha Augustin repeats in Creole every night to help her fall asleep.

He who dwells in the secret place of the Most High will dwell under the shadow of the Almighty. I will say to Jehovah: "My hope and my castle", my God, I will trust in him. his feathers will cover you and under his wings you will be safe; Shield and buckler is his truth.

She repeats it over and over and over again until she manages to diffuse her anguish and falls asleep inside the tent where she has lived for almost five months, in the El Chaparral camp, together with Salomón, her partner. She prays because it is not easy to rest here, a settlement in front of the checkpoint of the same name, in the midst of a pandemic; Pray for the more than three hundred migrant families, national and foreign, waiting for an appointment to enter the United States.

It is an afternoon in June 2021. Pedestrians cross the Tijuana River on the bridge known as El Chaparral, which connects the end of Avenida Revolución, in the tourist area of the city, with an esplanade of a shopping center in decay, practically abandoned, and meters ahead, under a vehicle bridge, the camp begins. Dozens of stores are lined up, one next to the other, in a block, with only a small corridor that allows zigzagging to enter the center of the place, where the heat of the afternoon — plus the smells of the concentration of several hundred people in conditions overcrowded — leave no room for fresh air. Perhaps that is why a group of people gathers on the ridge of José María Larroque street, where they have placed a table, a mirror and, at one end, they have improvised a small beauty salon. A couple of migrants wait to get their hair cut, shaved or braided; at the other end the women cook and distribute food. They communicate in Creole and do not have much interaction with people of other nationalities. The dangers in the place are constant; the tents and tarpaulins with which they improvise shelters on sidewalks or in the middle of the street do not provide security. The CNDH estimated that around three thousand people lived in El Chaparral in overcrowded, precarious conditions, without sufficient sanitary measures to mitigate the covid-19 virus. “The lack of food […] deepens their precarious condition. Neither have effective and permanent measures been implemented to prevent the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Girls and boys deserve special attention, just over a thousand in that place, as some are sent to ask for money at the border crossing line, while others are potential victims of sexual abuse and some more, infants, lack milk formulas for their food”, published in June 2021.

The people who settled here were encouraged by rumors that they would soon open the land border, which was closed on March 21, 2020, due to the pandemic. The announcement that the Joseph Biden administration would put an end to the Stay in Mexico protocol generated this expectation. Throughout two years, this immigration policy was applied to more than 72,000 asylum seekers, so that they would wait in Mexico for the resolution of their cases. Biden suspended her on the first day of her office, on January 20, 2021, and they began to enter droppers. But months later, in August, the United States Supreme Court ordered the government to reinstate it.

—When I am a merchant in Haiti, I sell a lot of things. A government group is coming, I speak ill of that party, I want to understand that party. They fight with me, they make a fire with my business. They say: "I am going to kill myself." I went to Port-au-Prince and they say anywhere I live, I'm going to kill,” Nathacha says, with many difficulties in her command of Spanish, about the reasons that led her to flee her country.

Nathacha left Haiti in October 2017. She migrated to Chile and her four children were left in the care of her sister, while she sent the salary she received as a day laborer in the blueberry picking fields to support them. When that job opportunity ended, Nathacha traveled to the northern border of Mexico with the intention of applying for asylum. He arrived on January 30, 2021 and since then, although he has tried, he has not been able to get a job. Nor has he been able to process temporary residence in Mexico, because he does not have enough money to pay the fees, which range from five thousand to 9,800 pesos. His remaining options involve living in a shelter or in this camp, and he has chosen the latter, because he believes that this is how he will be one of the first people the US government cares for.

She and other Haitians in El Chaparral have never even heard of the existence of Little Haiti. In fact, from Tijuana, Nathacha only knows the camp and has no interest in learning more. He speaks very little Spanish, he learned it when he lived in Chile. In Tijuana she has a fellow national friend who received her and among the relationships she has built during her stay is Salomón, her current partner, a Haitian who lived in the Dominican Republic. In Mexico he has no one else.

Racial tension is one of the biggest concerns for the Haitians in the camp. Coexistence has broken down between those who are “white” —as they are called— and those who are not, Afro-descendants. They complain of experiencing discrimination because some people have presented themselves as lawyers for organizations and have treated everyone except them. There have also been attempts at fights over the occupation and cleanliness of the space. In the place there is no authority assumed by the organization and there is no surveillance. Weeks before our visit, the Tijuana mayor's office removed public bathrooms and a community kitchen to encourage eviction. But that only made everything worse and, contrary to expectations, the migrants continue to arrive. Since then, those who can pay to eat and wash in nearby restaurants and hotels. The others improvise.

In the early morning of June 27, 2021, when most were resting inside their shelters, a group of men with their faces covered attacked the tents.

—They shouted: “Haitians, Haitians! They have one day to go!”—says Nathacha.

The attackers cut through the mesh of her house with a knife, destroyed her belongings and beat her. The same is said by other of his compatriots who fled that same morning. “I went to sleep with four friends. I'll come. If I start to wait, I'll wait for the whites to start breaking all the Haitian chaparas, that's why I didn't sleep,” Florence Nicolas, a twenty-eight-year-old Haitian who left after the attack, wrote in a WhatsApp message. a store. Weeks later he left Tijuana to live in another northern city, in Monterrey, Nuevo León.

After the attack, Nathacha also left the city. On July 24, he arrived in Matamoros, Tamaulipas, where in early September the media estimated the massive arrival of some two thousand Haitians who intended to cross through the Puerta de México International Crossing. There he has been waiting another month for his immigration situation to be resolved. He knows that it could take months for the US government to allow him entry and he does not want to return to the violence and precariousness that he experienced in Tijuana. She continues without a job, but her extended family from Haiti and the United States supports her to pay for the hotel where she now sleeps with her partner, Salomón.

—In Tijuana things didn't go well. Some are doing well and others are not. Not us.

His hopes are still pinned on crossing.

Before bed continue praying Psalm 91.

Haitian families attend Christian services on Sundays in different churches scattered throughout the city of Tijuana.

***

Haitian migration continues through Mexico. Activists, human rights defenders, and academics interviewed for this report agree that several waves have occurred and that there are differences in how the Mexican authorities responded to each one. “Migration never stopped, but there have been different stages: first [in 2016], when the first ones arrived; later, those who continued to arrive to reunite with their families and try to cross. In Tapachula, Haitians received an exit document from the imm for twenty days; at that time they could go up to Tijuana without being stopped. But there was a change in immigration policy in 2019: they stopped giving that document and increased militarization and arrests in Tapachula. That was also due to pressure from the Trump administration,” says Paulina Olvera, founder and director of Espacio Migrante. His opinion coincides with that of Soraya Vázquez, deputy director of Al Otro Lado: “In Mexico, entry and transit was not what it is now. There was no such repression or this idea of keeping people in the south. They actually allowed them to transit.” Now, Haitians face very different scenarios.

In September 2021, the repression with which the immigration authorities and the National Guard detained migrants in Tapachula made headlines again. Videos of the persecutions and violent arrests were disseminated on social networks and the media, including Haitian families with children.

Meanwhile, in the north of the country, with the changes in the Biden government's policies, with its twists and turns, uncertainty not only runs through Tijuana; At the close of this edition, the media reported the massive arrival of Haitians also to Matamoros and Reynosa, in Tamaulipas, which caused the saturation of shelters and the creation of new extremely precarious camps. Then they also arrived in Ciudad Acuña, Coahuila, with the intention of crossing to Del Río, Texas, where they were detained by the US authorities and the images of Border Patrol horsemen with whips, chasing migrants of African descent, caused a media scandal.

Mexican Foreign Minister Marcelo Ebrard said he would speak with Secretary of State Antony Blinken to discuss the recent flow of Haitians. “They come from Brazil and Chile, not from Haiti, they have refugee status in those countries. They are not requesting to be refugees in Mexico, except for a small percentage. What they are asking for is that they be given free passage, practically, to the United States," he told a conference.

This is a crisis of yesteryear added to the continued increase in violence and political instability in Haiti after the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse (occurred on July 7) and forced migration as a result of two natural disasters: the earthquake of July 14, August, which reached seven degrees Celsius, and Tropical Storm Grace, which hit the island a few days later. In addition to the border crossing closed to non-essential transit due to covid-19, it has also had an impact on "the total closure of most ways to safely request asylum at United States ports of entry," the Welcome Committee published. Of California.

To explain it, Vázquez lists three profiles of migrants trapped in Tijuana: those who had already started an asylum application and those who returned to wait in Mexico under the MPP policy; those who were arriving and intended to request asylum, but had to enlist to wait their turn; and to those who applied Title 42, a health order that prohibits the unauthorized entry of migrants or asylum seekers and that has been used during the pandemic. Against this last case, Title 42, civil society organizations are using a legal argument or exception to try to unblock the entry of asylees. “[With] this exception, people can enter under humanitarian admission, such as parole. It is being done by identifying the risk that the person is suffering here [in Mexico]. So, if you have a health problem, if you have a situation where you have been a victim of crime here, you feel threatened. The point is that everyone qualifies: all migrants are at risk here. Everyone”, says Vázquez and explains that in addition to proving their vulnerability, migrants must have someone to receive them in the United States and continue the litigation there.

The processing of the humanitarian parole as an exception to Title 42 before the US government is being carried out by lawyers from organizations such as Al Otro Lado through an online survey, but their capacity is limited. Even so, the migrants stuck on the northern border are crossing, dropper by dropper. Among them, Haitians. “They are admitting 250 people a day; we have processed 2,500. Among them, Haitians, Central Americans, other strange countries and Mexicans, above all, Michoacán”, calculates Vázquez. From February to August 2021, the organization received 1,975 requests for the humanitarian parole of 5,901 people. Of these, 608 (10.3%) were of Haitian origin.

Haitian families attend Christian services on Sundays in different churches scattered throughout the city of Tijuana.

***

Wilthene Pierre has been robbed thirteen times since he opened his typical Haitian restaurant, Kris Kabap, in downtown Tijuana in 2018. The place is modest: three plastic tables with artificial flower arrangements in the center, the menu covered in laminate, a small and disorganized kitchen in full view of the diners. Perhaps the greatest luxury is television. Even so, they do not stop looting it from time to time, says Wilthene, who does not stop carrying out his tasks. He points to the holes in the roof of the premises through which the thieves have slipped in and lists the losses: the television, the refrigerators, the pots, even soft drinks have been stolen. The food offered by the restaurant is basic: fried chicken or pork accompanied with white rice, beans, fried plantains and a small salad. The Haitian style is successful, especially among the Caribbean community that is not used to Mexican seasonings and spices. A couple of years ago this restaurant appeared in the media as an example of the successful economic and cultural integration of the Haitian community in the city. Notimex made a report that was replicated by several local media: "Restaurant, opportunity for Haitians stranded in Tijuana." Now, with the thefts and the pandemic, to sustain the premises, Wilthene has to reinvest the few profits in the sale of old iron, a lucrative business in a city that receives scrap metal from the neighboring country. In the area there are at least seven Haitian restaurants founded by Haitians. The one closest to Wilthene's changed ownership a few months ago because those who opened it migrated to the United States.

A few stores ahead is the Repondong Barbershop. The previous owner held the business for three years; a month ago, before crossing the border, he handed it over to Joseph Philogene, one of his employees. Joseph, who has lived in the city for four years, says that at some point he will hand it over to another Haitian, too, when he manages to cross. In addition to restaurants, hairdressers have been some of the most prosperous businesses for Haitians in Tijuana, says Joseph. The reason is that in Mexico there are no stylists who know how to cut and style the characteristic curly hair of Afro-descendants. This 33-year-old man says that the exodus of his compatriots is becoming more and more evident: at the beginning of 2021 they used to serve a hundred people from Monday to Sunday; now, a week, twenty-five are arriving.

***

Tijuana managed to be a plan B for thousands on their way north, but there were factors that made it stop being so. Suddenly, Tijuana was emptied of Haitians. The causes were, first, the discriminatory policy and police and military harassment towards people of African descent throughout Mexico, specifically derived from the deployment of the National Guard in border cities in June 2019. "A Haitian told us: 'Ya I have documents here, but I was leaving the factory where I work with my Mexican colleagues and they only stopped me and questioned me'. Obviously it is because he was a black person”, says Paulina Olvera, from Espacio Migrante.

Then, in second place, came the pandemic, which caused a great loss of jobs throughout the border and equally. The ban on essential crossings for more than a year and a half collapsed the cross-border economy. The economic losses in businesses in the area are estimated at 55 billion dollars, according to the Laboratory for Analysis of Commerce, Economy and Business of the UNAM.

Finally, on May 22, 2021, the US government resumed the TPS temporary protection program for Haiti. This meant again that there was the possibility of applying and not being deported and obtaining work permits there; although it is only applicable to those who crossed before the resumption of TPS. “[Haitians] already knew that this was going to happen, that it was going to be approved at some point, and they crossed over. Many who already had a regular status of stay, who were super-settled here, with a good job and so on, crossed over, because in the end their intention was always to be in the United States”, explains Vázquez.

It seems that what was socially called “Haitijuana” is on the decline. In Little Haiti there were families that settled for three years, some even had babies, and at the first opportunity they left. The settlement of the community in Tijuana, one of the most eclectic cities for being a scene of passage, was not exactly a rooting. Because what happened in Little Haiti also happened throughout the city. It wasn't a real establishment, just survival strategies, smart waiting plans.

—Two and a half years ago a Haitian told me: 'If they open the border, not a single Haitian will remain.' And that's how it's happening,” says Pastor Banda. Haitians have a mentality that they want to reach the United States and sooner or later they will achieve it.

Haitian families attend Christian services on Sundays in different churches scattered throughout the city of Tijuana.

***

Like every Sunday, with impeccably white heels, a jacket and handbag of the same color, a tight red dress, her hair tied up in a high bun and, as an extra detail, a red face mask, Mirlene awaits her husband and his friends. neighbors of Little Haiti to attend El Calvario Baptist Church, in the center, to listen to the service in their language. Edmond rushes out of the room and finishes tucking in his shirt while they wait for Remy and Cadilus —who returned to his room because they forgot their masks. Seeing them already all gathered, well dressed and in a hurry, it seems that the group is heading to a party.

Thirty-eight-year-old Mirlene, thin, small, and with a tough attitude, arrived in Mexico six months ago, in December 2020. She came from Brazil, where she lived and worked for two years in a pharmaceutical company —in Haiti she studied for a bachelor's degree in Pharmacology—so the job turned out to be a good opportunity. Edmond, for his part, has been in the country since 2018, where he has worked in maquilas. After several years apart, with a new US government supposedly more open, Mirlene decided to catch up with her husband to apply for asylum together. However, while they wait, the economic situation has forced them to live in the shelter. Edmond does not have a steady job or earn enough to pay rent, and she cannot get a job without her Mexican residency.

Two months ago, Mirlene began selling bread and coffee in the morning to those staying at the Embajadores de Jesús church; It also occurred to her to sell candy, popsicles, marzipan, peanuts: an entrepreneurial idea, because here children outnumber adults. At the entrance to the room where Mirlene and Edmond sleep, every day a line of children forms to buy at least one piece of gum for a peso, the cheapest in the repertoire. Mirlene tells them with monosyllables what is enough for them and what is not, and how much they owe her for what they choose.

She also receives cell phones to charge them in the electricity connection inside her room; It has a whole system of tokens to recognize the owners of the devices and charges ten pesos for delivering them with one hundred percent battery. This last service, she says, does not bring her any income, because every two months she pays the electricity bill, but they are one of the two families that have this privilege in Little Haiti.

Of her other life, in the other Haiti, Mirlene prefers not to speak. She is a reserved, cautious woman, she could come off as sullen. The only time she seems to let her guard down a bit and allow herself to be herself is when she attends church.

The El Calvario Baptist temple, in the Azcona neighborhood, holds two services on Sundays: the first, at nine in the morning, in Creole and is presided over by a Haitian pastor. Mirlene says that this is one of the two churches in the city that still share their facilities with Haitian pastors and faithful; the other is the First Baptist Church, which at the time was also a hostel and now is only a meeting place. El Calvario has a basketball court, a front patio and a modest construction with the capacity to receive seventy people and, in the background, a small stage where there is a lectern with the message: “Sanctify them in your truth. Your word is truth".

On this last Sunday of June, almost fifty Haitians of African descent who live in Tijuana arrived. Suddenly a musical group, accompanied by the voice of a woman who does the choirs, sets the religious ceremony on an emotional seesaw. They interpret a first song in Creole with parsimony. Then a man recites a long litany, and by the time he finishes, the music returns with a festive tune to which the audience dances and claps, culminating in a climax, with which everyone seems to connect. Laments are heard; several more cry.

—Hallelouya!—the ceremony guide asks them.—Hallelouya!—responds the audience.—Mèsi Seyè mwen! [Thank you sir].—Mèsi Seyè mwen!—they repeat.

In the audience, while she sings the songs, listens to the sermon and repeats the prayers, Mirlene stands with her back facing the wall. She does not seem to want to know anything about those around her and, at times, she enters a kind of trance. isolated.

Her fellow hostel mates also transform: they appear happy, festive, but then vulnerable, sorrowful. It is an act of intimacy and catharsis.

Meeting every eight days and disbanding after an hour, this community most closely resembles the real Little Haiti. They will return the following week, if their prayers are not resolved, if the wait in Tijuana continues.